Flow is impacted by many different factors, but the topics I'd like to touch on are communication, process, and culture.

Communication

In 1968, Conway observed: "Organizations which design systems are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations." This is known as Conway’s law. Worded a bit differently: Organizations which design processes are constrained to produce a process flow which is a copy of the communication structures between departments.

Conway also gives us the idea homomorphic force: “This kind of structure-preserving relationship between two sets of things is called a homomorphism.”

Software architectures are difficult to change, and so are organizations. It's not a very large stretch to suppose that these two things are self-supporting. Once software takes on the characteristics of the wider organization it will serve to reinforce the organizational structures, which in turn will strengthen the software architecture.

As organizations grow from a single engineering team to multiple teams, there appears to be a natural tendency to want to start to apply local optimizations by creating specialist teams that focus on specific problem areas. This specialization usually emerges as a result of the larger organization needing to manage priorities coming from multiple sources (customer support, legal, finance, and so on). Organizational lines are drawn, and engineering team structure often follows.

Here's an example on what that might look like

This type of organization probably looks familiar. You have a series of teams inside an organization with their own lists of priorities attempting to influence a series of product managers to get their asks prioritized across a set of compartmentalized teams.

To get a feature done, you need to talk to several PMs and influence the roadmap of several teams, and hope that all the items which touch your ask across functional component teams get done (hopefully close together in time) as well as worrying about all the inter-operability and integration points between the component teams. Then there's the whole release train that involves integrating the work, packaging it up, testing it somehow, and releasing to production.

Your engineering teams are 2-3 levels away from the consumers of the application, the chances of information loss in the telephone game is very high, which effectively means that you will often end up building solutions that aren't quite right.

Each group has competing objectives and incentives. Your marketing team wants a website update pushed out in time for a conference, your sales team is trying to close a big deal that includes a SoW that was a slight over-promise on a timeline, your support team is worried about a bug that has been opened a while back, etc... Each of these actors is pushing on PMs and teams that themselves have different priorities.

As the number of fingers in the pie increases, you might start to notice an increasingly fragmented set of experiences.

Component teams being pushed in different directions might start letting quality slip, throwaway code never gets refactored (if it ain't broke...) and some parts of the app start getting harder to change (testing cycle time increases, simple asks appear to take disproportionate amounts of time).

Process

As more and more things are getting started in parallel (in an attempt to get more stuff done in our agilefalls), we start to encounter another uncomfortable truth: The more we try to do in parallel, the slower velocity becomes. This is known as Little's law, and can be paraphrased as: If we have a consistent speed of things getting completed, the amount of time it takes to complete each item is directly proportional to the number of things we are working on. This concept applies at all types of work effort and all teams inside an organization (individual teams, feature level, organizational initiatives, etc...). From this lens, an impediment to flow is starting too many things simultaneously. Less (in progress) is more (in delivery).

None of this is necessarily pre-ordained, however I believe this to be a common pattern among early stage companies that have managed to achieve a certain scale without having been intentional about how they think about building their products and the organizational and process patterns to apply to guard against some of these pitfalls.

Going from a single agile/scrum team to multiple teams is often when most of these problems start to rear their heads as orgs need more speed in execution to continue growth. Having spent some time researching this, I've landed on the LeSS methodology. Here's how it addresses some of the communication/process/queuing issues above:

- Every team builds features from start to finish, eliminating cross-team hand-offs

- Removing hand-offs means less queues

- Building out cross functional teams that are involved in all parts of the SDLC means that inputs and voices are heard early in the product spec and prioritization phases, avoiding front-loading efforts on work items that get ruled out late due to technical constraints.

- Single backlog means that the entire org has a single pane view on what are the real priorities, no longer do you have PM/POs trying to "find work" for a component team.

Culture

In this section, I want to talk about the cultural sources of impedance to flow. There are a myriad of things that can go wrong here, but I'll focus on engineering and corporate culture.

Org sabotage

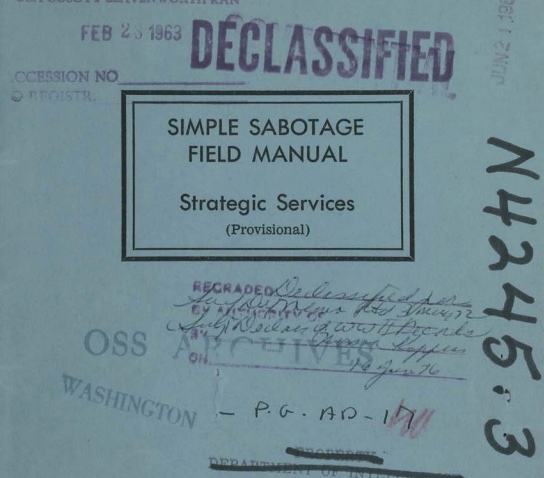

A small side-trip down memory lane: In 1944, the Office of Strategic Services published a field manual on how sympathizers could assist the war efforts by sabotaging organizations. This handy manual covered several different industries, and interestingly there is a ton of insight into how to make organizations fail and falter.

You can view the whole doc here.

Here are some gems:

- Insist on doing everything through “channels.” Never permit short-cuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions.

- Make “speeches.” Talk as frequently as possible and at great length. Illustrate your “points” by long anecdotes and accounts of personal experiences.

- When possible, refer all matters to committees, for “further study and consideration.” Attempt to make the committee as large as possible — never less than five.

- Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible.

- Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions.

- Refer back to matters decided upon at the last meeting and attempt to re-open the question of the advisability of that decision.

- Advocate “caution.” Be “reasonable” and urge your fellow-conferees to be “reasonable” and avoid haste which might result in embarrassments or difficulties later on.

- In making work assignments, always sign out the unimportant jobs first. See that important jobs are assigned to inefficient workers.

- Insist on perfect work in relatively unimportant products; send back for refinishing those which have the least flaw.

- To lower morale and with it, production, be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions.

- Hold conferences when there is more critical work to be done.

- Multiply the procedures and clearances involved in issuing instructions, pay checks, and so on. See that three people have to approve everything where one would do.

- Work slowly

- Contrive as many interruptions to your work as you can.

- Do your work poorly and blame it on bad tools, machinery, or equipment. Complain that these things are preventing you from doing your job right.

- Never pass on your skill and experience to a new or less skillful worker.

These are amazing markers and hints for identifying patterns of (un)intentional sabotage and a great list of things to be on the lookout for when trying to optimize organizations.

Seems like a great candidate for some old-timey war posters with these points as "things to look out for".

Culture of mastery vs. management career paths

Many orgs build out career paths that encourage engineers to strive to get into management as a path to more varied work, more responsibility, and often most importantly more money. This is quite often how great orgs turn into mediocre orgs, as this puts into play the Peter Principle. Simply stated, employees in orgs that focus on career path progression that places high value on management positions will tend to promote people until they are no longer competent, as skills between roles are often not transferrable. It's easy to imagine brilliant engineers being terrible managers and the cascading effects that has on team morale over time.

Also we must consider this: If you are promoting your most competent employees and not demoting the less competent employees, what is the net effect over time? One can surmise that the good folks fade, and the mediocre remain.

The take aways:

- Plan for leadership and develop those skills specifically. Switching from an engineering role to a managerial one should involve mastery of the management skills before switching roles.

- Have a clear career progression ladder. In it's simplest form: Eng I (Jr.), Eng II (Intermediate), Eng III (Sr.), Eng IV (Principle/Staff), Eng V (Architect) and list out expectations for each level.

- Promote people pro-actively once they are demonstrating that they are operating at a level above their current one.

- Promotions should be conditional on continued performance at the new role level and as such should update the employment contracts to reflect new expectations.

- Performance manage those not operating at the expected level. In the extreme, demote/dismiss.

- Plan for people wanting to switch roles within the organization. Help keep your great people as they journey through change in the work life, but do so intentionally. If a QA person wants to become a dev, or a dev wants to become a PM that's fine. They must do the work to learn the skills on their own, then demonstrate mastery before being considered. Also there has to be an open role.

Culture of engineering discipline over expedience

Build a PoC. Once you've demoed it, someone asks if it can be deployed to prod.

The customer loved it! And bought it! You've got 2 weeks to make sure it'll scale for big customer, our company will fail we can't get this deal!

One of the hallmarks of early stage companies unregulated growth in the name of expediency. There's always a reckoning though. Usually 2-3 years of this type of growth leads us to the spaghetti code jungle. There is a corollary here to the Peter Principle: over time, without intentional design the system will tend to reach a level of complexity at least one level above that at which it can be changed efficiently to meet new requirements.

Code becomes quagmire.

Usually this is because the quality of most designs is invisible to the users of the system (if it works, does it matter how badly built it is?). Justifying sweeping re-factoring or large architectural changes for the sake of future engineering efficiency are almost universally seen as frivolous engineering extravagance. Marching orders are almost always "deliver on time and under budget", and architecture is a luxury.

The agile "get out of quagmire" card is

- Continuous refactoring (if you're not going to plan very far ahead, be ready to change/fix/readjust things)

- Just in time architecture

- Reduce complexity by reducing scope (build small decoupled things)

- Tools enforce discipline (Automate testing, automate coding practices, automate all the things).

Another way of thinking of this might be to fund projects with ongoing spending in mind. When starting projects budgets should be allocated for ongoing costs for development for the entire lifetime of the project instead of up-front budgets that ignore ongoing solution maintenance.

Further reading

https://hackernoon.com/conway-is-killing-you-and-little-is-helping-750f3acfb60e